This week I have been developing a series of twenty six SOLO rubrics for exploring the Professional Standards for Primary Principals in New Zealand – rubrics for professional competencies around Culture, Pedagogy, Systems and Partnerships and Networks. I am quite pleased with the first draft thinking. I especially like how I have been able to align the SOLO levels with Charles Leadbeater’s For, to, with and by thinking. Contact me if you would like to join with other educators and test them in the real.

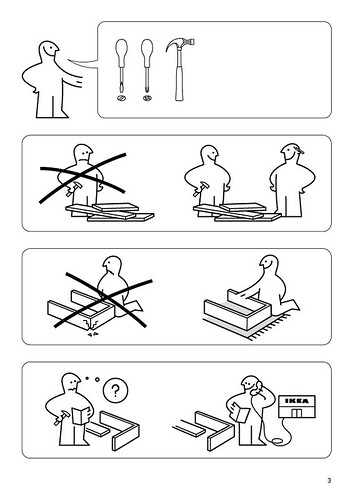

My next step is to build in an explicit reference to the IKEA effect described in Hattie and Yates Chapter 31 Visible Learning and the Science of How We Learn.

My next step is to build in an explicit reference to the IKEA effect described in Hattie and Yates Chapter 31 Visible Learning and the Science of How We Learn.

I am much enjoying this latest book from the inimitable Hattie – mostly for the measured way it addresses some of the latest must have – must do – approaches – extolled in the blogosphere and Twitterverse.

The book should carry a warning. It brings serious edu_myth busting content to the table.

My hope is that the chapters and their study guide questions are widely shared. They are catalysts for thoughtful professional discussion and prompts for revised imagining by educators all over.

The chapter on the IKEA effect is a good example. The IKEA effect was first identified by a business-oriented team of psychologists – Michael Norton, Daniel Mochon and behavioural economist Dan Ariely .

Hattie and Yates (2013) describe the IKEA effect as a situation that arises “whenever someone takes an active role in the production of a positive outcome, then he or she is disposed towards valuing that outcome more positively, even to the point of overly inflated assessment, which the person believes is true, fair and correct.” P306 Ch 31 Hattie and Yates 2013.

Noting that businesses have been highly successful with marketing strategies that use the IKEA effect to engage the consumer in some kind of effort- filled activity before the good can be enjoyed; they go on to describe the IKEA effect in education where the courses that are hardest to access (and papers that are the hardest to pass) are more highly valued than others.

Hattie and Yates address the implications (and role) of the IKEA effect (and the endowment effect) when giving effective feedback to students and beginning teachers. I can see how a similar approach will work with the rubrics I have been working on – when teachers are asked to give feedback on the professional competencies of their principals it will help if they approach the task with the IKEA effect in mind.

However, I am thinking about the educational implications of the IKEA effect in other ways

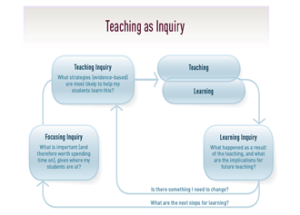

The teaching as inquiry process mooted in the New Zealand Curriculum p35 is popular in the schools I work with. I’d like to look at the implications of the IKEA effect on the outcomes of teacher inquiry. When teachers exert huge effort into their teacher inquiry – huge effort does not equate with dead ‘brill outcomes -huge effort equates with “greater love for” – and that cognitive bias is disquieting – even scary for the profession.

The teaching as inquiry process mooted in the New Zealand Curriculum p35 is popular in the schools I work with. I’d like to look at the implications of the IKEA effect on the outcomes of teacher inquiry. When teachers exert huge effort into their teacher inquiry – huge effort does not equate with dead ‘brill outcomes -huge effort equates with “greater love for” – and that cognitive bias is disquieting – even scary for the profession.

“The IKEA effect appears to be entirely the result of investing energy to complete a worthwhile project and then being able to stand back and admire its successful outcome. Simply working on a project, contributing to it without seeing it through to closure, does not appear to produce the effect at all.” P308 Hattie and Yates 2013.

This suggests that teachers who undertake teaching as inquiry like research will feel best about (most value) the inquiry when they are encouraged to integrate the outcome of their inquiry into their classroom practice in some way. And this thought makes me more than a little anxious that the IKEA effect will make it even harder for teachers to hear the caveat about teacher inquiry in Ben Goldacre’s keynote at ResearchED 2013

“One of the most depressing experiences I’ve had is talking to teachers who describe a research project they have poured their heart and soul into that is methodologically crap”. Ben Goldacre ResearchED 2013