I am thinking about epistemic knowledge – “ways of knowing”. How I get to add things to the “stuff I know” box – is interesting. It also requires me to think about the options for critical review of the “stuff” in the box. And then there is taking things out of the box. To ask, what are my criteria for deletion, and how as I get older do I acknowledge the increasingly important category of “I used to know, but now I’ve forgotten”?

It turns out my “ways of knowing” include: What I do to understand explain or justify the things I know. How I investigate, interrogate and validate the things I know. The processes I use to solve problems. How I accommodate paradox and uncertainty. And how I deal with other “ways of knowing” – ways that might conflict with my ways.

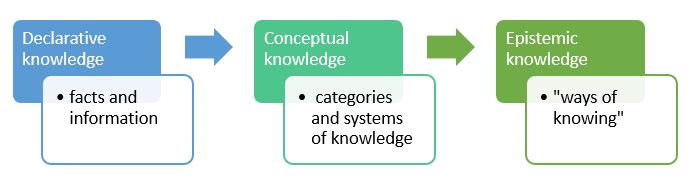

These “ways of knowing” are epistemic knowledge. They are the processes that allow us to establish knowledge. In a world where we have lost the universals and increasingly embrace intersectionality it is not surprising that these “ways of knowing” are increasingly categorised.

One category comes from our lived experiences, the values and beliefs (previous and current) of living with poverty; parenting many children; moving places or countries or jobs in a nomadic lifestyle; of being in a nurturing or manipulative relationship; or perhaps belonging to a religious community. We take these “ways of knowing” and use them to make sense of other aspects of our lives. For example, I have always often used the “ways of knowing” I developed from the years I spent sitting in the Playcentre sandpit with toddlers, lots of sand and only one hose – to understand the power plays in a staff meeting. Forget the conch – whoever controls the hose wins.

“Ways of knowing” can be cultural. For example, mātauranga Māori is a distinctive body of knowledge AND ways of knowing established from a Māori perspective – it represents a cultural way of knowing. It uses kawa (cultural practices) and tikanga (cultural principles) to make meaning of the world.

In schools “ways of knowing” have commonly been categorised by disciplines. Thinking like a historian, a mathematician, an artist or a scientist. For example…

Scientific “ways of knowing” are flexible and adaptive. Thinking like a scientist includes careful observation of phenomena and then drawing inferences or asking why it happened. Next scientists generate theories to explain the inferences; and then investigate how well the theories stand up to scrutiny through repeated rigorous experimental testing to determine if the theories are reliable and or valid.

As Mayr describes it: All interpretations made by a scientist are hypotheses, and all hypotheses are tentative. They must forever be tested and they must be revised if found to be unsatisfactory. Hence, a change of mind in a scientist, and particularly in a great scientist, is not only not a sign of weakness but rather evidence for continuing attention to the respective problem and an ability to test the hypothesis again and again.

It becomes apparent that central to a scientists’ “way of knowing” is the questioning of knowledge and opinions – being prepared to revise or change in the face of new evidence. So, thinking like a scientist is always about being open to changing what you think you know, in the light of new evidence.

When helping students understand disciplinary “ways of knowing” in the sciences it would be a mistake to think about “ways of knowing” as being fixed or ritualised processes.

For example, when your “ways of knowing” means everything you know in science is up for review, it is not surprising that methods for testing are privileged. But, teaching this in school risks introducing inflexibility. Anyone who has “done science” at school will dredge up memories of “the scientific method”. The steps in the “scientific method” are often memorised and ritualised. And yet this rigidity is counter to “ways of knowing” in science where the methods of testing themselves are always open to critique. In science, variations on the “as espoused in the textbook” method can be developed, compared with existing practices, and improved processes enacted.

The alternative – a ritualistic even obdurate or stubborn adherence to a “way of knowing” might have provided advantage in the past (or when introducing new ideas) but later it can risk leaving the “way of knowing” inert, inactive, an anachronism, a process without agency.

You can see this happening when students have an inflexible understanding of “the scientific method”. They can recall the process steps in the “scientific method” or “fair testing” but have no idea how or why to use them as a “way of knowing.” Certainty without understanding is not to be admired in science. Better is to understand that the scientific method is simply a place holder for the many different processes that can be used to test the reliability and validity of a scientific theory. The “ways of knowing” themselves can be held up for critical review and evaluation in the sciences.

And in a rapidly changing world, questioning assumptions in the “way of knowing” – the adaptive thinking of the scientist – is something of a “good thing”.