Concepts or “BIG ideas” are often used in schools to provoke and extend connections enabling a shift from surface to deep understanding. They can also be a first step to the deeper notion of “ways of knowing” or epistemic knowledge.

Concepts help students shift from “stuff I know” (declarative knowledge) to putting the knowledge to use in some way (application and then extension).

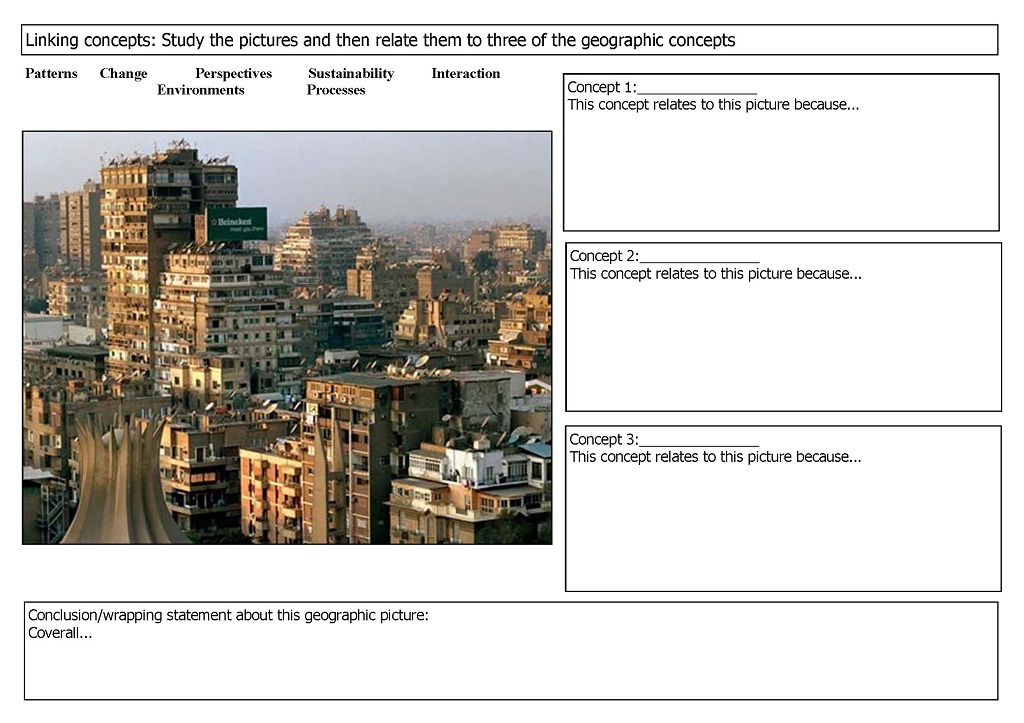

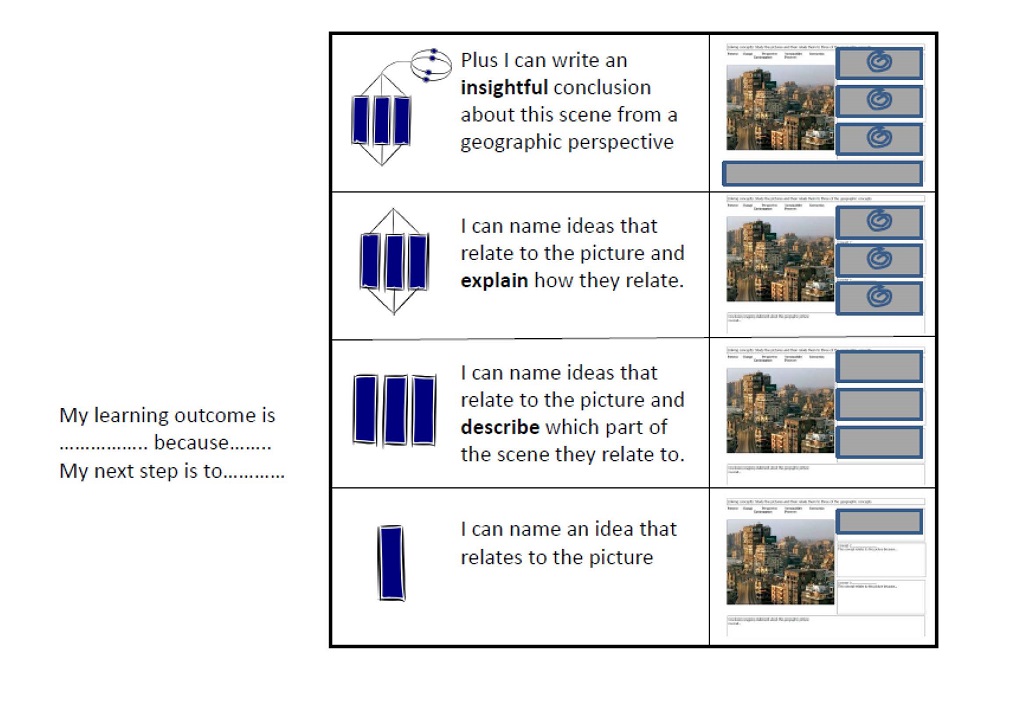

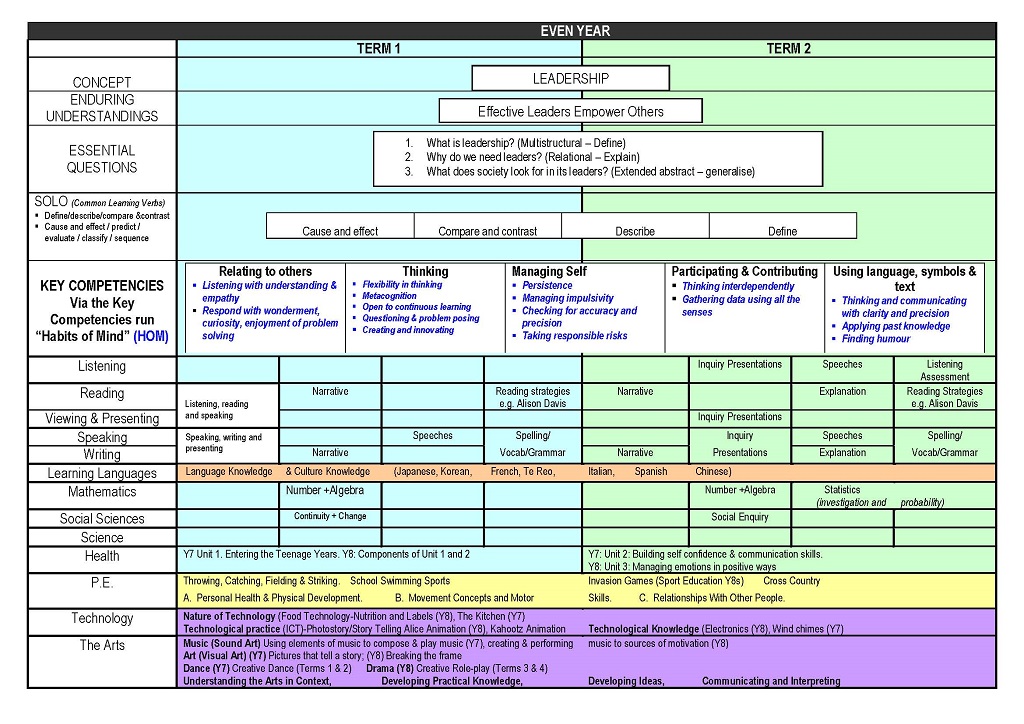

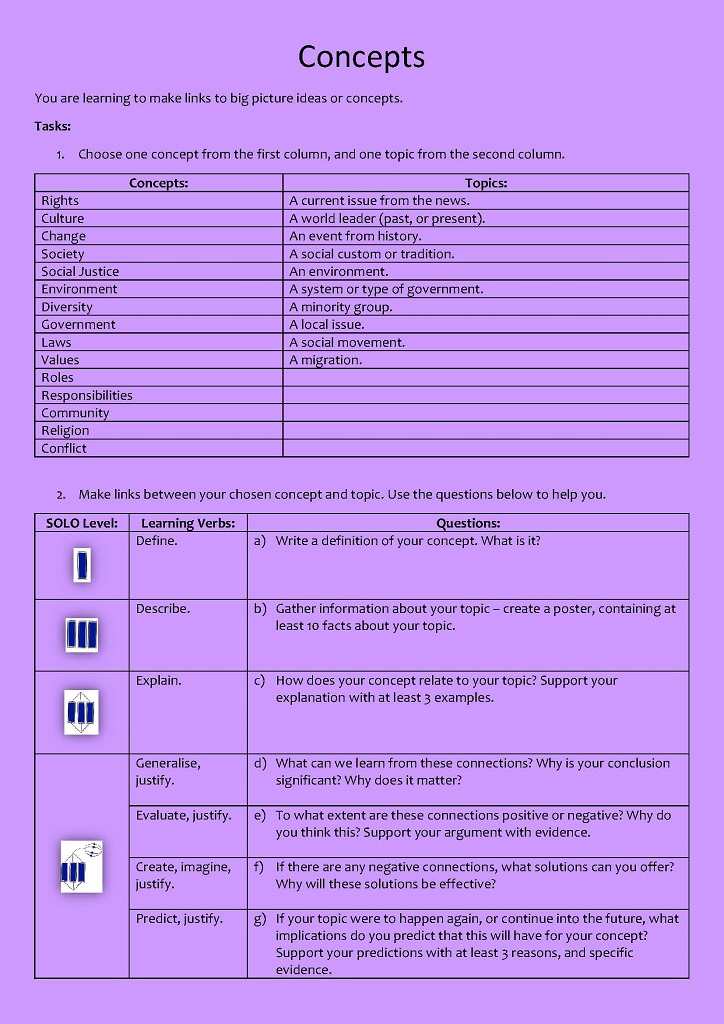

In my work I most often see schools using concepts as inert organisers of knowledge – for example – in strategies where students match a concept or BIG idea to the new learning – an event or a narrative – using SOLO templates (Fig. 1 and 2) or using SOLO Hexagons (Fig 3.) ; and as organisers on a curriculum mapping wall in staff workrooms where teachers talk about “a concept for the term” (Fig. 4) (Tasks at the SOLO multistructural levels of understanding).

It is less common for me to see students using concepts as active systems – for example when integrating ideas in problem solving and inquiry – concepts as things you apply (Tasks at SOLO relational levels of understanding).

I seldom see concepts used in ways that lead to far transfer of knowledge – transforming student understanding (SOLO extended abstract levels of understanding).

It is true that New Zealand schools design their student learning experiences around many different broad-brush values and belief systems but, this is infrequently if ever around “threshold concepts” for disciplinary understanding. This is a shame, because everything I read suggests that “threshold concepts” are catalysts for the deep disciplinary understanding we seek.

Biggs and Tang (4th Edition 2011 p92-93), promote their use when designing teaching and learning activities, in their popular text, “Teaching for Quality Learning at University, describing “threshold concepts” as follows:

“Whatever kinds of knowledge are being taught, there are some key concepts in a discipline that, once understood properly, change the students understanding of a whole area, sometimes dramatically. These threshold concepts as they are called, bring students to stand at the threshold, as it were of new broad-based understanding. They need to be isolated and emphasised in teaching. They are however, sometimes troublesome to teach because they make a break with the way the students have been looking at the content. It is important that teachers in a program discuss and agree what the threshold concepts are and how they should be taught.” (p.93 Biggs and Tang 2011)

A more whimsical description is seen in an opinion piece “Threshold concepts in practice” , where McGowan describes “threshold concepts” as enabling “intellectual wrangling” (McGowan, 2016). When I think about McGowan’s description, I always imagine preparing students to work with horses on the West Auckland sets for Hercules and Xena: Warrior Princess.

So, I am hoping that the educators working on the current review of the New Zealand Curriculum – Curriculum Progress and Achievement. will take advantage of the opportunity to move past the old concepts as disciplinary “BIG ideas” rhetoric and reference Meyer and Land’s “threshold concepts” across the different disciplines – so that NZ students can better engage in powerful “intellectual wrangling” across all the curriculum learning areas.

This is not an unreasonable hope. After all, “threshold concepts” are not new and they are not untested. Meyer and Land’s ideas have been around for at least 20 years and many researchers have explored the implications of “threshold concepts” in their disciplinary spaces. They are simply hard to identify and teach for – and classroom teachers engaging with a revised curriculum could do with a hand to target and overcome the many barriers in student disciplinary understanding.

It does not seem unreasonable to claim that explicitly addressing threshold concepts in the current NZ curriculum review has the capacity to powerfully lift the level of teacher professional development and pedagogical content knowledge around disciplinary understanding. This seems especially important with the increasing adoption of inter-disciplinary learning and collaborative group inquiry in New Zealand schools.

I recommend teachers who are curious, start by getting a paperback copy of Meyer and Land (2012) for their professional library and spend time with colleagues exploring the extensive resources at Threshold Concepts: Undergraduate Teaching, Postgraduate Training, Professional Development and School Education

Threshold concepts, are often associated with understandings that are beyond our direct perception – far extend imaginings involving spatial and or temporal scales, randomness, and probability. For example, an understanding of differing time scales and probability is necessary before students can fully appreciate natural selection and evolution (Tibell and Harms 2017).

So, playing in the background of my mind at the moment are the various ways in which educators can make this kind of thinking more accessible to students.